Thursday, December 29, 2011

quick 2011 year-ender post!

I've written about my media highlights of 2011 over at Yet Another Magazine.

Tuesday, December 20, 2011

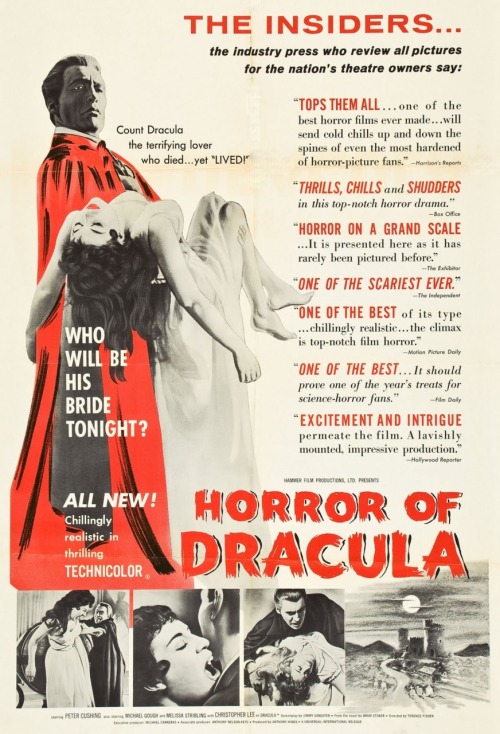

#12: Hidden Wars: Horror of Dracula (1958) and The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (1966)

Horror of Dracula, directed by Terence Fisher; and The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly; directed by Sergio Leone; do not seem to have much in common besides violence more colorful, bloody and brutal than that shown in their genre predecessors. Yet one is a war epic where no main character fights in nor cares about war. The other film -intentionally or not- acts out tensions that could have sparked war in the time it was made.

In the The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, the theme of civil war recurs in many character relationships. Brothers, business partners, fellow soldiers and others are divided by various interests and loyalties. There is also the actual Civil War, which rampages through the same south-western United States where our leads roam. Unlike most films set in this era, the three main characters do not belong to any side of the war. They pursue their own cons and hunts, exploiting local and state criminal laws and any other factors they encounter. The war winds in and out of the plot, saving one character from an otherwise inescapable fate, and spurring several scenes of interpersonal conflict or concern. Intensity built from personal interest and fate leads to a climactic shootout that could happen any time and any place. One look at the graveyard setting, though, shows that the film never escapes the ghost of war.

Bram Stoker’s Dracula and its many filmed adaptations begin with Jonathan Harker, an everyman real estate employee who unwittingly ends up in business with a vampire. Horror of Dracula turns Harker into a cognizant infiltrator. He poses as Count Dracula’s new personal librarian in order to fulfill a mission. While it’s amusing to think of a vampire count hiring a personal librarian (if he just wanted a warm-blooded person, he has the surrounding village to feed on), the important point is that position gets Harker within the Count’s castle walls. Who sent Harker on this undercover mission? Van Helsing, a man of science and faith, determined to fight against the godless creatures who feast on red blood. A scene with Harker’s relatives furthers the spy parallels when an official cannot reveal the true nature of a family member’s work and, to put it best, current existence status.

Agents of Dracula are hidden amongst the populace, and can turn loved ones into new recruits. Border guards are bribed and tricked in a vague Eastern European location. There is even a secondary character surnamed Marx- but while his funeral home plays an important part in the story, the character himself is just a jolly old man with dark humor. This Cold War framing does not extend to every aspect of the movie, and was probably not even a subtext intended by those who worked on the film. However, it adds a little layer of brain game to find Cold War parallels in an already entertaining horror film.

Under the surface, Horror of Dracula’s characters can be seen as agents of war between nations and ideologies. The main trio in The Good, The Bad, the Ugly dismiss that type of war. Violence is between solo fighters, inside and outside the army, and the antihero lead even calls one battle “a waste.” Dracula’s enemies fight for life and goodness, while Leone’s cowboys fight for life and gold. Both movies, however, operate on trust and free will. Whom you can trust and how long that trust can last?

Does the pursuit of a wealthy long life (or afterlife) foster personal freedom or destroy it? Is it worth the abandonment of family, or the deaths of others? Not even the unselfish Jonathan Harker escapes judgment, for while he works for the greater good, he leaves his family without a clue as to what might happen to him, and inadvertently endangers a beloved cousin. Leone’s trio are lone vagabonds with no care or nearly no care for others. There is an argument with a long-lost sibling who criticizes a main character for departing home to become a bandit. The argument brings up the needs of a group versus the needs of the individual, and it doesn’t end with complete triumph for either side.

Horror of Dracula displays excess in its bold colors (reputedly the first vampire movie to have bright red blood, and the second Hammer movie to include that feature after Curse of Frankenstein), low-cut eroticism, and the most lavish sets possible on a relatively small budget. It is traditional in all other ways, following a familiar story where good people fight one impulse-driven collective for the lives and souls of their own collective. The Good, The Bad, and the Ugly is packed with a large cast of extras and numerous locations. However, colors are dominated by blue and brown, muted by sun and dust. Flat landscapes and widespread vistas of sand eclipse all other sets. It is a long-running movie with a minimalist plot, savage and radical for the time but (with the other movies in Leone’s "Dollars Trilogy") a template for spaghetti westerns and other films to come. It is the relentless self-centeredness of the characters that give brief flickers of sympathy and partnership their grace.

Final battles, in both films, are fought over a grave- where all wars end. People in wartime, banding together and breaking apart- it is this theme these dissimilar films share.

They also share a hero's outfit of coat and scarf.

Horror of Dracula, directed by Terence Fisher; and The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly; directed by Sergio Leone; do not seem to have much in common besides violence more colorful, bloody and brutal than that shown in their genre predecessors. Yet one is a war epic where no main character fights in nor cares about war. The other film -intentionally or not- acts out tensions that could have sparked war in the time it was made.

In the The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, the theme of civil war recurs in many character relationships. Brothers, business partners, fellow soldiers and others are divided by various interests and loyalties. There is also the actual Civil War, which rampages through the same south-western United States where our leads roam. Unlike most films set in this era, the three main characters do not belong to any side of the war. They pursue their own cons and hunts, exploiting local and state criminal laws and any other factors they encounter. The war winds in and out of the plot, saving one character from an otherwise inescapable fate, and spurring several scenes of interpersonal conflict or concern. Intensity built from personal interest and fate leads to a climactic shootout that could happen any time and any place. One look at the graveyard setting, though, shows that the film never escapes the ghost of war.

Bram Stoker’s Dracula and its many filmed adaptations begin with Jonathan Harker, an everyman real estate employee who unwittingly ends up in business with a vampire. Horror of Dracula turns Harker into a cognizant infiltrator. He poses as Count Dracula’s new personal librarian in order to fulfill a mission. While it’s amusing to think of a vampire count hiring a personal librarian (if he just wanted a warm-blooded person, he has the surrounding village to feed on), the important point is that position gets Harker within the Count’s castle walls. Who sent Harker on this undercover mission? Van Helsing, a man of science and faith, determined to fight against the godless creatures who feast on red blood. A scene with Harker’s relatives furthers the spy parallels when an official cannot reveal the true nature of a family member’s work and, to put it best, current existence status.

Agents of Dracula are hidden amongst the populace, and can turn loved ones into new recruits. Border guards are bribed and tricked in a vague Eastern European location. There is even a secondary character surnamed Marx- but while his funeral home plays an important part in the story, the character himself is just a jolly old man with dark humor. This Cold War framing does not extend to every aspect of the movie, and was probably not even a subtext intended by those who worked on the film. However, it adds a little layer of brain game to find Cold War parallels in an already entertaining horror film.

Under the surface, Horror of Dracula’s characters can be seen as agents of war between nations and ideologies. The main trio in The Good, The Bad, the Ugly dismiss that type of war. Violence is between solo fighters, inside and outside the army, and the antihero lead even calls one battle “a waste.” Dracula’s enemies fight for life and goodness, while Leone’s cowboys fight for life and gold. Both movies, however, operate on trust and free will. Whom you can trust and how long that trust can last?

Does the pursuit of a wealthy long life (or afterlife) foster personal freedom or destroy it? Is it worth the abandonment of family, or the deaths of others? Not even the unselfish Jonathan Harker escapes judgment, for while he works for the greater good, he leaves his family without a clue as to what might happen to him, and inadvertently endangers a beloved cousin. Leone’s trio are lone vagabonds with no care or nearly no care for others. There is an argument with a long-lost sibling who criticizes a main character for departing home to become a bandit. The argument brings up the needs of a group versus the needs of the individual, and it doesn’t end with complete triumph for either side.

Horror of Dracula displays excess in its bold colors (reputedly the first vampire movie to have bright red blood, and the second Hammer movie to include that feature after Curse of Frankenstein), low-cut eroticism, and the most lavish sets possible on a relatively small budget. It is traditional in all other ways, following a familiar story where good people fight one impulse-driven collective for the lives and souls of their own collective. The Good, The Bad, and the Ugly is packed with a large cast of extras and numerous locations. However, colors are dominated by blue and brown, muted by sun and dust. Flat landscapes and widespread vistas of sand eclipse all other sets. It is a long-running movie with a minimalist plot, savage and radical for the time but (with the other movies in Leone’s "Dollars Trilogy") a template for spaghetti westerns and other films to come. It is the relentless self-centeredness of the characters that give brief flickers of sympathy and partnership their grace.

Final battles, in both films, are fought over a grave- where all wars end. People in wartime, banding together and breaking apart- it is this theme these dissimilar films share.

They also share a hero's outfit of coat and scarf.

Tuesday, September 6, 2011

#11: A World of Horror: Vampyr (1932), At Midnight I'll Take Your Soul (1964), Black Christmas (1974), The Plumber (1979), The Thing (1982), A Tale of Two Sisters (2003), Meokgo and the Stick Fighter (2006), and District 9 (2009)

This post is for the World in Film Blog-a-Thon.

Representing Europe, and serving as a bridge from silent film horror to the sound era, is Vampyr, directed by Carl Theodor Dreyer. It was shot as a silent movie but had dialogue added in post-production. This film takes a Sheridan Le Fanu vampire story as the basis for dreamlike exploration of a setting where death seeps into place and mind. Vampyr is a prime example of the use of striking images in horror.

At Midnight I'll Take Your Soul (À Meia-Noite Levarei Sua Alma), directed by José Mojica Marins, represents South America. It is reputed to be the first horror film made in Brazil. The director also stars as Zé do Caixão (Coffin Joe), a nihilist-leaning undertaker who is violently obsessed with finding an ideal mate. This first film in the "Coffin Joe Trilogy" shows how engaging execution of an extreme concept can help an obviously low-budget film endure as a cult classic.

North America is represented by the Canadian film Black Christmas, in which a sorority house is targeted by an unknown killer. It predates better-known Hollywood cousins like Halloween by several years, and its influence can be found throughout the slasher subgenre. The terror in this film escalates from start to finish, and the group of sorority girls under attack are livelier and better-defined characters than many of the victims in other movies.

For Australia, there is the made-for-TV film The Plumber, written and directed by Peter Weir. Some might classify it as more suspense than horror, but this battle of wills between a housewife and an intrusive plumber finds scares in the most realistic situation on this movie list. Though it doesn't attempt greatness, Weir fit some complexities into this small-scale story, such as various levels of socioeconomic conflict and the ambiguity over what is permissible in the classification and expulsion of an outsider.

Antarctica is represented by The Thing, which focuses on a science team who finds an alien creature in the ice. Horror director John Carpenter keeps action and special effects grounded within an environment of isolation and paranoia.

Representing Asia is A Tale of Two Sisters (Janghwa hongryeon), directed by Kim Jee-Won. It's a gorgeous puzzle of a film that blends both psychological and supernatural varieties of horror.

Finally, we have Africa. While it was difficult to track down available horror films from the continent, I remembered that Neill Blomkamp's sci-fi film District 9 has a very strong body horror element. The film's commentary on race relations and xenophobia may be undercut by its depiction of Nigerian immigrants, but the messy divisions between outer-space alien refugee and human are still powerfully illustrated within District 9's narrative.

The last film on this list is the short film Meokgo and the Stick Fighter, directed by Teboho Mahlatsi. It didn't seem right to represent Africa just with a film that features a white African protagonist, so I decided to include this short film, which features black African characters. Like District 9, it's not strict horror. This odd little film is probably best categorized as fantasy. However, I'm also including it to bring up the point that horror, sci-fi, and fantasy often mix. Genre borders are probably imposed more by the audience than the creators, and are determined not simply by story, but a film's particular treatment of a story in relation with other films. This bizarre (at least to mainstream Western audiences) but entertaining short is about an accursed stickfighter who fights evil with the help of his magical tiny accordion (concertina). It is awesome.

This list was created with the intention of not only covering different continents but different types of horror cinema as well. Each selection is not meant to be an encapsulation of the entire horror output of a continent - just an outstanding film that happens to be from that continent. It's also worth noting the various fears that these movies depict. Black Christmas functions on fears of the intruder within the home. Vampyr, The Thing, The Plumber, A Tale of Two Sisters, District 9 and Meokgo and the Stick Fighter also make antagonists out of the outsider while incorporating suspicions about the protagonists themselves. The protagonists of At Midnight I'll Take Your Soul and Vampyr are driven mad by their fear of death, while the sci-fi films The Thing and District 9 find horror within bodily transformation. The outsiders are either possibly ordinary folks -sometimes the protagonists- whose perceived traits are exaggerated by possibly irrational fears, or extraordinary beings whose existence seems impossible until asserted with violence.

While one can't expect all stories to fit neatly within established categories, I've found that stories that are declared "horror" can be pared down to tales of defending minds and bodies against forces of unknown potential for destruction. An audience is whisked away from mundane and complicated everyday life and dropped into a fight for life and sanity versus the undefinable. It is the heightened return to instinct that makes horror such a vital genre.

|

I decided to participate in this blog-a-thon under the theme of horror. Let's start with the oldest movie first.

Representing Europe, and serving as a bridge from silent film horror to the sound era, is Vampyr, directed by Carl Theodor Dreyer. It was shot as a silent movie but had dialogue added in post-production. This film takes a Sheridan Le Fanu vampire story as the basis for dreamlike exploration of a setting where death seeps into place and mind. Vampyr is a prime example of the use of striking images in horror.

|

| Picture via poisonedteacup. |

|

| Picture via elbergo. |

For Australia, there is the made-for-TV film The Plumber, written and directed by Peter Weir. Some might classify it as more suspense than horror, but this battle of wills between a housewife and an intrusive plumber finds scares in the most realistic situation on this movie list. Though it doesn't attempt greatness, Weir fit some complexities into this small-scale story, such as various levels of socioeconomic conflict and the ambiguity over what is permissible in the classification and expulsion of an outsider.

|

| Picture via The Criterion Mission. |

Representing Asia is A Tale of Two Sisters (Janghwa hongryeon), directed by Kim Jee-Won. It's a gorgeous puzzle of a film that blends both psychological and supernatural varieties of horror.

|

| Picture found via The AV Club. |

Finally, we have Africa. While it was difficult to track down available horror films from the continent, I remembered that Neill Blomkamp's sci-fi film District 9 has a very strong body horror element. The film's commentary on race relations and xenophobia may be undercut by its depiction of Nigerian immigrants, but the messy divisions between outer-space alien refugee and human are still powerfully illustrated within District 9's narrative.

The last film on this list is the short film Meokgo and the Stick Fighter, directed by Teboho Mahlatsi. It didn't seem right to represent Africa just with a film that features a white African protagonist, so I decided to include this short film, which features black African characters. Like District 9, it's not strict horror. This odd little film is probably best categorized as fantasy. However, I'm also including it to bring up the point that horror, sci-fi, and fantasy often mix. Genre borders are probably imposed more by the audience than the creators, and are determined not simply by story, but a film's particular treatment of a story in relation with other films. This bizarre (at least to mainstream Western audiences) but entertaining short is about an accursed stickfighter who fights evil with the help of his magical tiny accordion (concertina). It is awesome.

This list was created with the intention of not only covering different continents but different types of horror cinema as well. Each selection is not meant to be an encapsulation of the entire horror output of a continent - just an outstanding film that happens to be from that continent. It's also worth noting the various fears that these movies depict. Black Christmas functions on fears of the intruder within the home. Vampyr, The Thing, The Plumber, A Tale of Two Sisters, District 9 and Meokgo and the Stick Fighter also make antagonists out of the outsider while incorporating suspicions about the protagonists themselves. The protagonists of At Midnight I'll Take Your Soul and Vampyr are driven mad by their fear of death, while the sci-fi films The Thing and District 9 find horror within bodily transformation. The outsiders are either possibly ordinary folks -sometimes the protagonists- whose perceived traits are exaggerated by possibly irrational fears, or extraordinary beings whose existence seems impossible until asserted with violence.

While one can't expect all stories to fit neatly within established categories, I've found that stories that are declared "horror" can be pared down to tales of defending minds and bodies against forces of unknown potential for destruction. An audience is whisked away from mundane and complicated everyday life and dropped into a fight for life and sanity versus the undefinable. It is the heightened return to instinct that makes horror such a vital genre.

Sunday, August 14, 2011

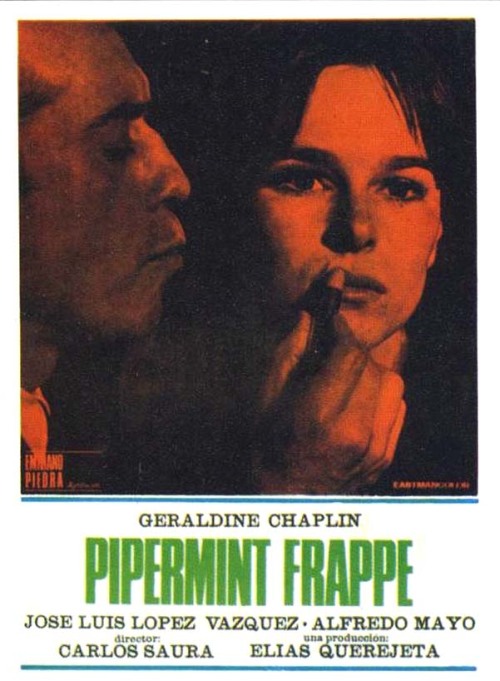

#10: The Ideal Woman: Peppermint Frappé (1967) and Pygmalion (1938)

Peppermint Frappé (1967), directed by Carlos Saura, and Pygmalion (1938), directed by Anthony Asquith and Leslie Howard, are two films in which men attempt to shape a living woman into their feminine ideal.

Peppermint Frappé follows the doctor Julián (José Luis López Vázquez) in his pursuit of Elena (Geraldine Chaplin), the glamourous new wife of his best friend Pablo (Alfredo Mayo). Elena proves to be a difficult prize to obtain, so Julián induces Ana, the shy nurse he works with (also Geraldine Chaplin, excellent in double roles), to become an imitation of Elena, feeding his obsession until he wins over the real thing.

Peppermint Frappé follows the doctor Julián (José Luis López Vázquez) in his pursuit of Elena (Geraldine Chaplin), the glamourous new wife of his best friend Pablo (Alfredo Mayo). Elena proves to be a difficult prize to obtain, so Julián induces Ana, the shy nurse he works with (also Geraldine Chaplin, excellent in double roles), to become an imitation of Elena, feeding his obsession until he wins over the real thing.

Pygmalion, originally a stage play by George Bernard Shaw, was adapted for the screen by the playwright himself. Professor Henry Higgins (Leslie Howard), a master of dialect and accent, bets that he can transform the poor "guttersnipe" Eliza Doolittle (Wendy Hiller, in a star performance) into a society lady whose origins none would question.

The comedic drama of Pygmalion trots at fine speed, with dialogue and images flying fast until particular moments demand more settled, slow emphasis. The psychological tension of Peppermint Frappé creeps onto the screen, beginning with a title sequence set over fashion photos cut for collage. The action is set at a meandering pace; but judicious use of sharp cuts, soundtrack, and intense 360-degree spirals gently draw the viewer into unsettling emotional territory.

In Peppermint Frappé, the camera subtly blends Julián's stalker gaze with a distanced perspective that monitors his movements. If Julián cannot possess Elena's body, then he can possess her essence: through photographs, through her personal effects, and through Ana. These are visual and tactile ties to Elena. Julián's apartment is richly furnished, every object handled with meticulous attention to proper appearance and use. He also keeps a room in an abandoned mansion in the country, yet while the rooms he uses are clean and well-decorated, the rest of the home is left to ruin. Julián has an expert eye for crafting places and people into his idea of perfection, but has no care for what does not please him.

Shaw's reworking of the ancient Greek legend has the Pygmalion figure, Henry Higgins, craft his Galatea figure Eliza through speech instead of sculpture. This shift from a visual to verbal focus is an ingenious method of adaptation to the stage, where dialogue reigns. Though dress and gesture are also important in Eliza's transformation, words are Professor Higgins' forté, and serve as the entry point for his social experiment. Unlike Julián, Higgins initially embarks on this project with only his personal pride in mind. Higgins selects Eliza out of the challenge given by her low-class accent and place in society, not the looks and unapproachable aura of Elena or the desperate nature of doppelganger Ana. When Higgins realizes that he is falling in love with Eliza, it not the perfect society doll he desires, but the independent Eliza, who appreciates the skills she's gained but violently defends her status as an independent human being.

Both Julián and Henry are selfish and think little of the feelings of their female subjects. These men either overlook or never realize their own flaws, though both films present them as far from faultless. The intended audiences of the men's experiments differ: Henry holds his "improvement" of Eliza to his impossible standards but he seeks to make Eliza perform for those in high society. Julián's efforts are only for himself. (One makeup scene makes the viewer wonder if, as a balding and withdrawn middle-aged man, he ultimately jealous of the beauty of young women. His taste for something as sweet as the title drink suggest a little girl's tastes.) However, one can say that since only Henry and those close to him -who wager that he won't succeed- know the truth behind the elegant Ms. Doolittle, the project is ultimately for entertainment and pride of Henry. What makes Henry Higgins a more appealing protagonist than Julián is that, along with avoiding darker impulses, he is only obsessive about his work and does not seek to possess Eliza.

Elena is the embodiment of '60's mod style, taking her time to maintain her appearance even in private. Whether this effort is for herself or to please the eyes of others is not made clear. Yet her constant upkeep is not Julián's all-consuming devotion; she is a free spirit who enjoys life and her husband's company. Elena's husband may occasionally call her a "child," but they are both honest with each other and the relationship appears to be mutually beneficial. Some might think of Elena as a prototype of the "Manic Pixie Dream Girl" found in indie-oriented literature and film, but Elena's refusal to bend to Julián's will works against the wish fulfillment of that trope. Though Julián finds Ana a malleable stand-in for Elena, their personalities are drastically different, each frustrating Julián in an alternate way.

Eliza, despite her lack of education, has a sound mind that Henry notices in their early meetings. She willingly agrees to take the free elocution and manners lessons Henry offers, and is the one who approaches Higgins after the initial chance meeting. She puts in a greater amount of effort into Higgins' experiment, for both personal pride and her dream of being a respectable owner of a flower shop. Though they live in restrictive societies -1930's England and Franco-era Spain- Eliza and Elena both exercise agency.

Another writer could further this comparison by investigating the films' settings and their varying qualities of the feminine ideal. Yet both films share the theme of pride: both the healthy pride in one's skills and attributes, and the harmful pride that blinds one to reality and to the feelings of others. Peppermint Frappé presents the male gaze as toxic, and serves as a surreal fable about treating women as objects. Pygmalion sets forth the notion that all people, regardless of gender or class, should be treated with respect.

Another writer could further this comparison by investigating the films' settings and their varying qualities of the feminine ideal. Yet both films share the theme of pride: both the healthy pride in one's skills and attributes, and the harmful pride that blinds one to reality and to the feelings of others. Peppermint Frappé presents the male gaze as toxic, and serves as a surreal fable about treating women as objects. Pygmalion sets forth the notion that all people, regardless of gender or class, should be treated with respect.

Tuesday, March 22, 2011

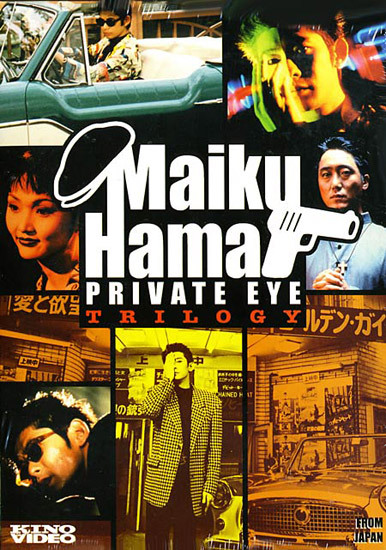

#9 - The Maiku Hama Trilogy (1994-1996)

To participate in the Japanese Cinema Blogathon, I decided to abandon the double-feature format for a triple-feature: the Maiku Hama: Private Eye trilogy. There isn't much written in English about these movies, and I hope that will change someday, because these movies are fun.

Named after the Mike Hammer character created by writer Mickey Spillane, Maiku Hama (played by Masatoshi Nagase) is a private detective who's both comic and strangely cool, with unfashionable shirts and a beautiful yet malfunctioning American sportscar. He has connections all throughout Yokohama, though not all of them are happy to see him, and his office is located inside a movie theater - where the stingy owner demands you buy a ticket before entry.

This trilogy is a pastiche of numerous film tropes and references. It's often described as a parody and homage to American gangster pulp, French New Wave, and Japanese yakuza movies. However, the trilogy forms an experience totally its own. Consisting of the films The Most Terrible Time In My Life (Waga jinsei saiaku no toki), Stairway to the Distant Past (Harukana jidai no kaidan o), and The Trap (Wana), it's a bizarre combination of quirky humor and dark detective drama. It also has a catchy jazz theme song..

The character, played by Nagase, was renamed Mike Yokohama in the somewhat-connected follow-ups Mike Yokohama: A Forest with No Name (directed by Shinji Aoyama) and the TV series Shiritsu Tantei Hama Maiku.

The Trap is my favorite entry in the Maiku Hama trilogy. Just as Maiku seems to have finally found good luck in life -business going well, wonderful girlfriend, sister doing alright- a mysterious new case brings the series into the realm of psychological thriller. Four young women are dead, looking like department store mannequins with frozen expressions and no signs of harm. The police are baffled, and as Maiku investigates the case, he finds himself considered a possible suspect in the crime.

While there are some odd bits in this installment (for example, a major gangster boss villain in the past two films is suddenly a helpful Catholic priest in this one, with no explanation), the movie maintains a high level of suspense and terror that made me forgive minor faults. This film's plunge into horror reminded me of Takashi Miike's works in that genre, but what transpires here is a breathtaking and twisted creation all its own. With a clever use of parallels and one of the scariest killers I've seen on film, The Trap is a fantastic end to the Maiku Hama trilogy.

ETA: The Yokohama Nichigeki theater featured in the movies was closed in 2005.

- - -

This post was done for the Japanese Cinema Blogathon, created to aid relief efforts for those affected by the recent earthquake and tsunami that hit Eastern Japan.

Named after the Mike Hammer character created by writer Mickey Spillane, Maiku Hama (played by Masatoshi Nagase) is a private detective who's both comic and strangely cool, with unfashionable shirts and a beautiful yet malfunctioning American sportscar. He has connections all throughout Yokohama, though not all of them are happy to see him, and his office is located inside a movie theater - where the stingy owner demands you buy a ticket before entry.

This trilogy is a pastiche of numerous film tropes and references. It's often described as a parody and homage to American gangster pulp, French New Wave, and Japanese yakuza movies. However, the trilogy forms an experience totally its own. Consisting of the films The Most Terrible Time In My Life (Waga jinsei saiaku no toki), Stairway to the Distant Past (Harukana jidai no kaidan o), and The Trap (Wana), it's a bizarre combination of quirky humor and dark detective drama. It also has a catchy jazz theme song..

The character, played by Nagase, was renamed Mike Yokohama in the somewhat-connected follow-ups Mike Yokohama: A Forest with No Name (directed by Shinji Aoyama) and the TV series Shiritsu Tantei Hama Maiku.

Though all three movies were directed by Kaizo Hayashi, each film has a strikingly different tone. The Most Terrible Time In My Life is shot entirely in black-and-white Cinemascope, and starts off as an offbeat comedy about a rough-edged good guy detective with an amazing streak of bad luck. A case brought by a Taiwanese waiter brings both budding friendship and the unwelcome attention of the New Japs, a gang formed by immigrant Chinese and Koreans. The movie segues into a noir-soaked tale of loyalty, and it surprised me by exploring the subject of immigrants trying to make a living amidst prejudice in Japan. The introduction of a femme fatale into the story is initially jarring, but during the last act I found myself riveted by what was happening onscreen.

The second film, Stairway to the Distant Past, is shot in color Cinemascope. It begins with the same light tone that introduced its predecessor. Then enters the stripper Lily (Haruko Wanibuchi), the mother who abandoned Maiku Hama and his sister. At the same time, Hama finds himself drawn into the escalating political and criminal conflicts over control of Yokohama's port interests. The use of color seems to usher in a sensibility that's both more romantic and more jaded than that of the first movie. Things aren't just black and white and grey; they're complicated across the spectrum. While the violence in the first movie was made up of brutal close-range attacks, this second film goes all-out into action territory, complete with multi-level gunfights and a high-speed chase down the waterfront. Don't let this dissuade you story-minded viewers - Stairway to the Distant Past is indeed bigger in scope than the first film, but it's also more personal, dealing with Hama's own family and memories instead of those of his client. There's also a haunting scene, set amidst mannequins in a deserted alley, that serves as a taste of the movie to follow.

The Trap is my favorite entry in the Maiku Hama trilogy. Just as Maiku seems to have finally found good luck in life -business going well, wonderful girlfriend, sister doing alright- a mysterious new case brings the series into the realm of psychological thriller. Four young women are dead, looking like department store mannequins with frozen expressions and no signs of harm. The police are baffled, and as Maiku investigates the case, he finds himself considered a possible suspect in the crime.

While there are some odd bits in this installment (for example, a major gangster boss villain in the past two films is suddenly a helpful Catholic priest in this one, with no explanation), the movie maintains a high level of suspense and terror that made me forgive minor faults. This film's plunge into horror reminded me of Takashi Miike's works in that genre, but what transpires here is a breathtaking and twisted creation all its own. With a clever use of parallels and one of the scariest killers I've seen on film, The Trap is a fantastic end to the Maiku Hama trilogy.

ETA: The Yokohama Nichigeki theater featured in the movies was closed in 2005.

- - -

This post was done for the Japanese Cinema Blogathon, created to aid relief efforts for those affected by the recent earthquake and tsunami that hit Eastern Japan.

|

| The donation page is here. More participating blogs here. |

Tuesday, January 4, 2011

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)