|

| picture source |

|

| picture source |

As the post comparing the two shows remained incomplete, I noticed similar themes appear in other other genre (or "genre-leaning") television. In Penny Dreadful, True Detective's first season, Orphan Black, Äkta människor (Real Humans), Sky Atlantic's Fortitude, as well as the shows covered in this previous post (Utopia, Les revenants, and the first season of Hannibal); characters ponder the circumstances of their own existence. At what point did things turn wrong? How much of it is due to themselves, their upbringing, or current surroundings? Were they doomed at creation?

(spoilers under the cut)

True Detective's and Fortitude's tortured detectives and townspeople face and become figurative demons, a situation further complicated when people in Fortitude undergo horrifying physical transformations. Orphan Black 's clones struggle to assert their individual human lives within their status as scientific property. Äkta människor's "hubots" and Penny Dreadful's manmade or cursed creatures debate how much claim they have on humanity, and if being considered human is worth any effort.

|

| picture source |

Through the hypocrisies of men like Marty and the reactions of women like his ex-wife Maggie (an underrated and underused Michelle Monaghan), the show tries to make statements about misogyny and the relegation of females to background vices and victims. However, the show rarely develops those females beyond background vices and victims.Fortitude handles assault in a more respectful manner, giving significant time and respect to the surviving victim's perspective and lingering trauma, and not just the effects upon the male authority figure involved. The show seems to understand a woman's wariness of the romantic interests of a man who can wield institutional power over her, for even if he is sincere about his best intentions, they can appear similar to dangerous behavior. He cannot expect his feelings to be returned (as happens too easily in many media romances in which a pining "good" guy is entitled to requited affection) without her genuine attraction, trust, and understanding. While not revolutionary, the show also features many women of different professional social roles, from youth through middle age, with scenes focused on their own stories and decisions apart from the men in their lives. Even jealousy between two women over a man doesn't erupt into catty arguments; those women blame the men more than each other.

Yes, Penny Dreadful is centered around Eva Green as the powerful yet tormented lead, Vanessa Ives. The second season has the magnetic Helen McCrory as its villain, the witch Evelyn Poole, and the formidable Patti LuPone as Vanessa's mentor. However, the show seems to take a step back for every one or two steps forward in its treatment of female characters. Caliban's harassment of women is both called out but then somewhat excused by his outcast status. In the second season, the show correctly genders Angelique one episode, digs at her "disguise" and birth name the next, and is eventually is killed off to further a male character's story. While the show allows men of various sexual orientations to live, women suffer and die to further the stories of others- almost always a male character. The show can be even more Victorian than intended - condemning the state of psychiatric care and men's dismissal of women's concerns, but perpetuating the hysterical possessed woman trope and indulging the male gaze. Most of women's power comes from their magic. Females can only strike back through fantasy empowerment. When another character is brought back to recalls the abuse she suffered and witnessed throughout her life, she makes strong speeches decrying the treatment of women one minute, then displays her newfound power in alternately brutal and seductive ways upon men the next, lest her roaring rampage of revenge not be attractive.

Äkta människor is not faultless in this or in other regards, particularly with some gratuitous nudity in the opening episodes, but is better at showing a greater variety of female experiences through both sympathetic and distanced moments. Nearly all of the many female characters are developed in ways not entirely dependent upon their relationship with male characters, these females often interacting with each other in their own independent roles.

One complaint I have about the more-or-less competent English-language remake, Humans, is that, in incorporating elements of Flash's storyline into Niska's character, the writers decided to drop their version of Niska into a synth (their version of "hubot") brothel so that she will be "safe" in a place where no one suspects her. No longer is she the cool and commanding leader of the original, able to keep fellow hubots hidden in the countryside. She never turns off her pain receptors, and becomes enraged enough to kill one of her customers. This version of Niska does get a potent parting line when she leaves the human madam: "Everything your men do to us, they want to do to you."

Yet it's distressing that, in setting up her upcoming path of violence, they have to inflict sexualized horrors upon her (even if the underwear shots weren't always as lingering and exploitative as in other media works) to justify her anger. This sets up paths that could lead first to these audience trends of sympathy and then horror: 1) that she's only so angry and brutal because she was hurt, not just because she believes in synth free will and independence and 2) we have to witness this pain inflicted upon a named character in order to believe it, not a) trust the offscreen story of a victim or b) see that unnamed characters deserve their justice too, like what happens to a hubot Leo modifies in the Swedish original. Flash’s comparative ordeal Later on in the show, a man activates the sex function on Anita. The show contrasts the act with the daughter, Mattie, slapping two teenage boys for turning off a synth in order to have sex with it. She calls them disgusting for essentially trying to rape an unconscious synth. Yet, later on, while the newly-resurfaced Mia personality is visibly uncomfortable around the man, they soft-pedal the act, laying part of the blame on the Anita, who couldn’t do anything. It's also sad that another character had to suffer a higher level of sexual violence in the remake than she had faced in Äkta människor.

|

| edited from picture source |

Hubots are built with a variety of customizable physical functions, and aside from being general servants and laborers, they are often used as sex objects. Even humans who insist upon a romantic connection with hubots have considerable power and ownership over any hubot who hasn't received the code for free will. While we do see male hubots forced into porn and sex work, it is the female hubots who are most mistreated. Though they have more strength than the average human (and several female hubots do attack those who exploit them), they can be overcome by surprise, human knowledge of hubot weaknesses, and programmed submission to human commands.

Flash, for example, initially thinks that her pimp's attentions are genuine appreciation, but later recognizes that she is being abused. She later takes charge of her destiny, reinventing herself as the social climber Florentine. Mimi is fetishized for both her hubot status and Asian female appearance, and faces several assault attempts. The hubots we see seem programmed for heteronormativity--particularly traditional-minded Flash, who is offended by the presence of a lesbian married couple (differently-minded individuals with separate personalities and subplots in their own right). As Flash becomes the more accepting Florentine, aspects of her traditional child-rearing are taken to extreme ends, but her desire to live a domestic life and take care of children are not devalued by the show either.

While Rick, a male hubot who is illegally "upgraded" in sexual and personality functions, is exploited as well, he is adjusted to fit a hyperagressive male ideal. He becomes obsessed with control, reacting sometimes with violence and also stalking a random woman before his functions slowly break down during his pursuit. Though Rick's storyline is a metaphor for one way men are abused in real life, his once-desirable "alpha male" reprogramming placed special focus on dominance over women, and when he hurt men, it was to attack any man who threatened that sense of dominance and overall superiority.

Orphan Black features one actress, Tatiana Maslany, playing over a dozen characters who struggle to assert and define themselves against the institutions that try to control them.

"In its subject matter, “Orphan Black” broods on the nature-nurture debate in human biology, but in its execution, the show cleverly extends the same question to matters of genre. What does the exact same woman look like if you grow her in the petri dish of “Desperate Housewives” or on a horror-film set in Eastern Europe? What about a police procedural? The result is a revelation: Instead of each archetype existing as the lone female character in her respective universe, these normally isolated tropes find one another, band together and seek to liberate themselves from the evil system that created them.Maslany's characters are never easily contained in a single descriptive phrase: boho-geek scientist, soccer mom, tough grifter, troubled cop, trans male fugitive, ditzy manicurist, etc. Even a brief appearance has moments to deepen the dynamics beneath the veneer of a stereotype. [placeholder] A few women played by other actresses get their own arcs and interactions as well, particularly the foster mother and former militant Siobhan Sadler (Maria Doyle Kennedy) and conflicted double agent Delphine Cormier (Evelyne Brochu). The men get various supportive or antagonistic roles, though the male Project Castor clones are somewhat undercut by lack of character definition, even with the intent of showing how they were molded by a shared upbringing and military training.

By structuring the story around the clones’ differences, “Orphan Black” seems to suggest that the dull sameness enforced by existing female archetypes needs to die."

--The Many Faces of Tatiana Maslany, The New York Times

Among the Project Leda clones, we see two more divergent examples of nuture as programming for a strict agenda: Helena and Rachel. Both first appear as antagonists-- Helena trained to kill clones, Rachel groomed to control them. Helena, left in the care of nuns who practiced extreme corporal punishment, is later taken in by a fanatical sect that takes the words of religion to justify her murders, stating that the clones’ existence as an aberration, that only Helena is the true and blessed “angel.” Rachel, raised with full knowledge of her status as a clone, is encouraged by a company that takes the words of industrialized science to justify their power, stating that the clones are experimental products, that only Rachel is the special “pro-clone.” We see that these women hurt their sisters -as well as others- because are trained to see themselves as the superior exception, akin on a level to real life behavior in how women are often complemented by putting down other females, not being superficial or weak “like other girls.”

|

| edited from source |

None of these programs handles in-show race issues as well as they could, even considering that they are mostly set around white characters. Penny Dreadful in particular has no excuse. For a show that calls out Victorian mores, the slaughter of American Indians, and the deeds of its Great White Hunter archetype in Malcolm Murray, it is straightforward and oblivious in its neglectful treatment of the character Sembene. Is there any self-awareness when, in two seasons of deeper investigation into main and side characters, the only character who isn’t white is a strong and often silent generically African servant whose actions are nearly always in support of the white characters, whose backstory is suddenly revealed to be that of a slave-seller, and whose last act is to state that his life is worth less that that of the white man accompanying him? At least Danny Sapani displayed great presence and chemistry in the role. The third season has cast more people of color in recurring roles, but viewers should prepare to be intrigued and disappointed once again.

True Detective takes a more vague approach to depicting race relations. A historically-Black church, for instance, is burned and desecrated, but this action happens offscreen, and the detectives only arrive to size up the aftermath for clues in the larger investigation. As the years progress, secondary and tertiary African-American characters have more screentime and authority, with Detectives Gilbough and Papania resuming the season’s main case years after the all-white police team had declared it solved. There is also one scene in which a black woman who worked in the house of a powerful suspect gives testimony of the occult festivities celebrated on the estate. While others dismiss her as simply old and crazy, the detectives recognize her importance as a living witness, respecting her work and her years along with the truth present in her words, even if she ends with shouts of praise for The Yellow King. It’s a rare scene of consideration for someone probably seen as less important due to her race and social position. Also, the famous six-minute tracking shot momentarily has Cohle trying to save a black boy caught in a gunfight between white bikers and a mix of black criminals and civilians. Otherwise, True Detective seems very shy in onscreen confrontation in regards to race, or even mentioning casual racial bias. The show doesn’t have to go out of its way to show racism, or boldly state “now we’re integrated,” but this quiet and vague approach is a major contrast to how the show displays the other abuses of white men in Louisiana. Perhaps this is more tasteful than its treatment of sexism, and perhaps the writer might have failed in aiming further, but such a manner might be too timid and disrespectful for the world and themes it wants to depict.

The Arctic town of Fortitude is populated by a plausible mix of nationalities: Norwegians (and probably other Scandinavians) along with Irish and Russian workers, a variety of British people (including mixed-race households), and perhaps a few other Sami besides the taxidermist Tavrani. The two people who stand out most in this mix are Eugene Morton, an American working for British police to investigate deaths on the island, and Elena Ledesma. Ledesma is a Spaniard whose characterization initially treads close to exotic stereotypes: a sensual and olive-skinned Southern European with an accent that contrasts with the Northern Europeans around her. Her beauty attracts attention, much of it unwanted, and she becomes somewhat of a femme fatale. An affair with the married Frank Sutter inadvertently leads to his son’s illness and involvement in a murder, and suspicions and envious assault of a rival from Sheriff Anderssen. It’s a relief that later episodes develop her character beyond her allure; also sizing up Anderssen’s attraction, violence, stalking and other unlawful actions as of his own making, not hers.

The black characters on the show hail from the UK, and show some personality and independence beyond their relations to white characters in their own side of the storyline. Frank Sutter and son Liam are main characters, although Liam might be considered more of a conduit for plot. Trish Stoddart may only appear for a few episodes, but she outlives her white professor husband Charlie (though he is played by top-billed Christopher Eccleston). Scientist Max Cordero doesn’t get much screentime, but he seems to the reasonable and relatively decent half of the oil-prospecting duo sneaking about (the other half being Yuri, a somewhat stereotypical Russian security chief with a scary-funny extreme personality).

|

| picture source |

Orphan Black is better than many North American and UK shows at presenting many variations of white women, and makes an effort in regards to respectful LGBT representation as well. Its treatment of race, though, needs more work. Detective Art Bell (Kevin Hanchard) does have a significant supporting role, and is more-or-less included within the “Clone Club” inner circle of trust. Vic (Michael Mando) was also a recurring character, although he started off as an abusive ex-boyfriend that Sarah fights hard to escape. His criminal activities, messy personality, and obsession with Sarah are later played for comedic effect. One can also argue that Cosima’s dreadlocks, though appropriative, are very true to her character as a Berkeley bohemian who can arrogantly proclaim what is and is not acceptable. However, aside from Sarah and Helena’s generically African immigrant birth mother Amelia, who is soon killed by Helena, the two women with notable screentime who aren’t white are villains.

In the third season, Marci Coates is a pretentious and homophobic local representative whose school redistricting plans enrage Alison enough that Alison starts her own campaign to run against Marci. The show might have had an open casting call for the character, but having a black actress (Amanda Brugel) be the face of a practice often used against poor communities, especially those with a high minority population , is troubling combined with all the other factors in the suburban storyline. The show also spends more time saying that Alison cares about her kids Oscar and Gemma --adopted children of African descent-- than actually showing her with those children. They make cameo appearances or interact with their latest babysitter more than, in contrast, Sarah interacts with Kira, from whom Sarah’s often separated. Alison and her husband Donnie also have a twerking scene that parodies “gangsta rap” videos, throwing around money from their sudden drug-dealing fortune. The scene is meant to be hilarious and show how ridiculous the Hendrixes can be, but it seems everyone in the production was oblivious to the implications of uptight white suburb-dwellers celebrating the sale of drugs by breaking from their usual behavior and trying to copy a dance and video style that originated with African-Americans. What seems more intentional is having Alison’s mother suspiciously ask if Cosima is “mulatto” - we understand that the writers want to show the mother as not only overbearing and manipulative but racist as well, even if she has black grandchildren.

I’m criticizing what seems to be unnoticed or dismissed as okay by the writers, like the presentation of a stereotypical Mexican cantina, or when the show edges toward bizarre xenophobia when Alison and Donnie face intimidating Portuguese gangsters. While Portuguese are considered white Europeans today, they are light olive-skinned with accents exotic for the WASP standards of the suburbs (by which even nonwhite residents abide), playing fado in a dingy garage office. They are killed offscreen by another heavily-accented European, Helena, but since she’s now on her sisters’ side, it’s treated positively, with a bit of macabre humor.

Dr. Virginia Coady (played by First Nations actress Kyra Harper) does have an intriguing role and amount of power as the doctor overseeing Project Castor. Yet she rarely gets to interact with other women, except when she’s in conflict with them. She also encourages the Castor sons she raised to infect women through sex as part of an experiment - and doesn’t mind if her boys actually rape the victims, because it’s all in the service of trying to save the world . Of course a morally-gray villain is always welcome in drama, and there are women who sanction misogyny, but once again the show brings up unfortunate parallels and casts a minority face at the head of the practice, this time with real-life scientific abuses of forced sterilization and other horrors wrought upon American Indians and other populations.

On Äkta människor, Mimi's plight is reminiscent of many women, especially women of color, who are captured by human trafficking, sold into brothels or home service and face disrespect and harassment even in a more "respectable" white-collar workplace. Yet what happened to the immigrants? We see a diverse array of faces around, even in the hubot-hating "Real Humans" movement, but the show only covers the replacement of domestic jobs by hubots, and never mentions if the existence of hubots has discouraged or had any other effect on immigration from other European countries or abroad. The English-language remake overlooks the matter in a similar fashion.

|

Tobbe meets with a group of people who call themselves “Transhumans,” who frame their affections for hubots, and the disdain the rest of society has for them, appropriating terms used by the actual LGBT movement for the struggle of being a teenage boy in love with a female sentient robot. This group is also reminiscent of Japan-obsessed "weeaboos" in how they co-opt the pastels and stereotypical physical movements and vocal tics in their "hubot apprecation.” They are probably included to parallel scenes following the the extreme “Real Humans” movement, to depict people throughout the spectrum of hubot acceptance as a metaphor for current-day conflicts about immigration and other issues. Whether or not the show has an outsider’s ambivalence on the “hub-bies” is debatable, but the presentation of Tobbe’s attraction to Mimi as a struggle of sexual orientation is unconvincing, a cop-out to gain “progressive” sympathy by having a character who would otherwise not be discriminated against experience metaphorical discrimination. It’s disappointing to hear the priest Åsa’s message to her congregation as well as Inger’s defense in season 2’s climactic trial hinge upon simplistic comparisons of racism with discrimination against hubots. The show, while admirably tackling major issues, tends to treat all kinds of discrimination with the same weight in nearly all circumstances, without more precise context and nuance to strengthen its arguments.

The synths played by actors of African descent in Humans, Max (Ivanno Jeremiah) and Fred (Sope Dirisu), have more definition and screentime than Marylyn and Fred in the original version. While Max is seen first as Leo’s loyal helper, the show later reveals that the conscious synths consider themselves all Leo’s family, and breaking the trope of a minority character dying to further the narrative, it is saving Max from death that forms the climax of the first season. However, Fred’s body is twice immobilized and used against himself, turning what could have been commentary on exploitation of bodies, especially those of Black men, into a lazy reused trope.

Even with these criticisms, I wouldn’t have watched all these seasons through if I didn’t find something to enjoy or at least appreciate (I did feel wary about True Detective season 2 trying too hard with grim dark dramatics, and much of the reaction confirmed my opinion to stay away.) Yet it is not fiction for those who experience prejudice to treated as a lesser human for aspects of identity beyond their control; to see themselves in popular fiction as just helpful or harmful supporting cast to the privileged, if not narrative devices with little character of their own. For shows that grapple with the themes of humanity, this uneven handling of issues undercuts their ambitions. Perhaps it is more difficult for them to push their themes beyond general theories of existence towards a wider, but still story-relevant, range of matters of lived experience.

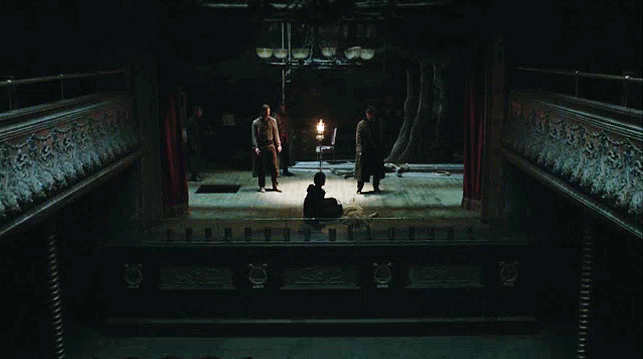

It is much easier for these shows to explore lives and other creations gone awry, current forces clashing with those of the past. While much corruption begins in the past, preserved for generations in True Detective or for eons in Fortitude, modernity doesn't alleviate misery, and can even compound it. Caliban delivers this monologue to his creator, Victor Frankenstein, in the third episode, “Resurrection:”

I am not a creation of the antique pastoral world. I am modernity personified. Did you not know that’s what you were creating? The modern age. Did you really imagine that your modern creation would hold to the values of Keats and Wordsworth? We are men of iron and mechanisation now. We are steam engines and turbines. Were you really so naive to imagine that we’d see eternity in a daffodil? Who is the child, Frankenstein? Thee or me?The conflict born in created sentient life continues in alternate present days, as in the hubot world of Äkta människor (Real Humans) and the clone conspiracy of Orphan Black. Time can be positive, and it can’t be denied as an important factor in the production of these series. These television programs of the past few years might not have existed outside what many like to editorialize as “The Golden Age of Television,” although every decade of television had its own quality programs. Various factors of creative control allowed for the writers, directors, and other crew of all the shows I’ve mentioned to put forth their ideas in at least one season‘s worth of episodes. Feats of technology (cameras and cosmetics) work with the actors’ skills to make clones and hubots and aging and combined locations believable for today’s eyes. Within the shows themselves, the passage of time can bring uplifting ends-- though years have passed, justice is finally served, truths are eventually revealed, and so on. However, the ambition to create and innovate, for personal as well as societal benefit, brings about results whose sentience threatens concepts thought essential to civilization and survival. Often, this threat is increased by reactions birthed from fear, but whatever the catalyst, the conflict escalates to points where extreme opposites form, where one type of living being finds that their existence cannot continue as they wish until the other is controlled, if not eliminated.

Death in all of these shows is brutal, both in the moment and in later trauma, and to seek motivation or escape through desire often complicates matters further with more people to care about and protect, when that desire is not itself destructive. The clones and hubots have defects, the detectives have demons, the monsters are swayed to violence by man. Even on Fortitude, a seeming utopia where there has been no violent crime and no one is allowed to die, there is biological corruption preserved in the ice, its danger heightened by the secrets the humans keep. Any blame is shared, by unconscious agreement, between innate and surrounding nature As I noted in my earlier post about Utopia, Les revenants, and Hannibal's first season, nature is an unavoidable and unending presence, that even when corrupted by humans, can still persevere and attack.

|

| picture source |

This returns us to the cosmic horror themes of True Detective's Rust Cohle and the Yellow King, that the actions of humans are nothing to the universe, whether for good or ill. But are the actions of characters nothing to their audiences? These shows are created by humans, shaped by a multitude of forces whose influences are intentionally and unintentionally incorporated into the work. We continue to follow these characters as guided by writers’ sympathies, by how much information is displayed or withheld. We may disagree with the way a show turns, when we feel that a line of dialogue or a choice is at odds with the characters and themes the show has fostered. Yet we will keep on watching as long as the creations, beyond the limits and biases of their creators, have compelling lives of their own.

YAM-Mag reviews of: True Detective - Season 1, Orphan Black - Season 2, Fortitude - Series One,

Hannibal - Season One, Utopia - Series 1, Les revenants - season one; and comments on Hannibal - Season 2, Äkta människor, and Utopia - Series 2.

ETA, May, 2016: The latest episode of Penny Dreadful , "A Blade of Grass" brings up the theme (paralleled by Frankenstein's and Jekyll's experiments) of abusing contemporary notions of psychology and psychiatric science to render people --particularly women-- docile, acceptable and exploitable to others. ETA, September 2016: However, by the series finale, Vanessa Ives has her agency completely removed from her until she (SPOILER) lets herself die at the hands of another.

No comments:

Post a Comment