After spending some time watching and researching the prose-to-screen adaptations directed by Wojciech Has, I decided to write about Has’s collaborations with author Stanislaw Dygat: 1958’s Farewells (Partings, Lydia Ate the Apple, Pożegnania) and 1959’s One-Room Tenants (Wspólny pokój). I’ll also compare these adaptations with another adaptation of Dygat’s work: the 1967 Janusz Morgenstern film Jowita. These titles are all studies of society under pressure, defined by spaces and a particular time.

What

characterized Stanislaw Dygat as a writer? According to Czesław Miłosz, Dygat’s

first novel Lake of Constance “was

directed at puncturing all the national clichés and the search for authenticity.”

The novel fictionalizes Dygat’s own internment under the Nazis, who sent him to

a low-security camp due to his French citizenship. “Dygat, with his humorous

detachment, is no exception among Polish writers of the postwar years. They

approach even the most hideous reality with a typically Polish mixture of the

jocular and the macabre.” [18] Along with his short stories, novels, and plays, Dygat adapted several other

works for other films. Like Wojciech Has,

Dygat refused to express affiliation with any party, but still voiced criticism

of the status quo. Dygat, however, did so after joining and then resigning from

the Communist party.

Dygat

adapted his 1948 novel Pożegnania for Has. Its title has been translated

into English as Farewells, Goodbye to the Past, and Lydia Ate the Apple. As the film begins,

a young man named Pawel is spying on a kissing couple on the street from his

upper-floor window. They leave by carriage before Pawel’s attention is called

back into the room, toward reality and his duties. It is early 1939. Pawel, a student

from an aristocratic family, is verbally reminded to follow through on his

family’s plans for his studies and career. After this stern warning, Pawel

heads for a nightclub. Romance develops between Pawel and the club escort Lidka.

One time in the nightclub, the song “Pamiętasz, była jesień (Do you remember,

it was fall)” plays, a popular song that happens to mention the film’s title, “Pożegnania,”

in the second stanza:

Odszedłeś potem nagle, drzwi otwarte

Liść powiewem wiatru padł mi do nóg

I wtedy zrozumiałam: to się kończy

Pożegnania czas już przekroczyć próg

Then you left suddenly, the door ajar

A wind-blown leaf fell at my feet

And then I understood: here it ends

It is time to cross the threshold of parting [3]

They soon

escape to the countryside. Pawel’s father catches the couple in an inn, and

pays Lidka to lead a more respectable life elsewhere. Lidka leaves on a train, and

the screen fades to Pawel lying in bed.

Gone is

his clean-shaven, in-a-suit look; he is clad in a black turtleneck, with

stubble on his face. Pawel rises in a room unfamiliar to the viewer. Details of

the new setting seep in: cramped and makeshift living conditions, soldiers

patrolling outside the window. It is early 1945. The city is under German control,

with heavy forces to come. Pawel has escaped from Auschwitz. When he reconnects

with his family, he discovers that Lidka married his cousin, and that the

couple plans to escape from Poland.

Only the

abstract of Wojciech Świdziński’s 2007 Kwartalnik Filmowy essay “Farewells-What does Wojciech J. Has did [bid] Adieu to?” is translated into English.

Yet even this paragraph offers worthwhile points to consider:

“Wojciech Jerzy Has began to reflect on the structure of time with his film 'Farewells'. The director was having a poetic dialogue, lined with irony, with the national tradition and prose of Stanisław Dygat when he made a film that entered the canon of the Polish school [author’s note: referring to the “Polish Film School” movement, discussed later in this piece], but at the same time stayed on the sidelines. Has was more interested in searching for lost time and observing how people, places and things had vanished than in History. The love affair of the film heroine and hero, Lidka and Paweł, is almost literally run over by the column of Soviet tanks in the closing scenes of the film. What mattered more was the game the pair was playing when they met each other and parted – it’s almost a sophisticated waste of new chances.” [23]

The two

times are set in contrast. Yet even before the war, the characters are trapped

by society and circumstance in one building or another, the nightclub or a

family home. Lidka and Pawel’s room at an inn only served as refuge for a

single night before they were discovered. In 1945, Pawel’s remaining extended

family has gathered in the same mansion, and even non-related refugees are

sleeping in the parlor. If those outside the landed class had to consider money

in all matters –including romance– before the war, the war exacerbates the

situation. Everyone becomes connected to the black market, and even aristocrats

must concern themselves with the grubby business of basic survival. Conversations

only occur when people need someone to talk with, or talk at; with growing

reluctance to touch on the dreams and distractions of years before.

Mieczyslaw

Jahoda’s camera work captures baroque touches in the looming paintings and sculptures. Key moments are

often shot through windows, or with a foreground character looking towards the

background. Compositions settle into Has’ typical tight diagonals and odd

triangles or triangular spirals. The soft diffused light and hushed grace,

however, differ from much of the deep-focus dark drama of Has’ other work, even

from Jahoda’s extraordinary transitions from realism to heightened reality on

Has’s feature debut The Noose, or the

theatrical visual shifts Jahoda and Has employ in The Saragossa Manuscript.

While

reportedly not too strict in adapting the story, allowing Has’ images their

strength, Dygat incorporates lengthy full quotes from his novel into the script.

This quotation technique occurs in other Has adaptations before and after his

collaborations with Dygat, regardless if Has or another person wrote the

screenplay. For example, “…in Farewells

the main characters stand at a bar and hold a conversation by quoting verses from

Slowacki at one another.” [25] This instance of quotation-reference also gives

some context to the themes Has and Dygat explored. Juliusz Słowacki was a Lithuanian-born 19th-century

poet and dramatist of the Polish Romantic movement, which reacted to collapsing

old orders and strict Enlightenment rationality with introspective ruminations

on spirit and nature. “Since the

oppressive hothouse conditions which fostered Polish Romanticism in the first

place have continued in many respects to the present day, the Romantic

tradition still reigns supreme in the Polish mind.” [2] Romanticism, in this

view, is fostered by tumultuous times despite any shattering of ideals; whether

it is the 18th century, WWII, or a particularly restrictive period

of Communist rule.

Over the course of the film, Lucjan’s illness strikes back, and he eventually cannot rise from his bed within the crowded apartment. “This is a very sad story about the creative feebleness of promising beginner artists, but also about the disease which deprives the main character, Lucjan, of hope for a better life.” [8] What I could find about the source novel in English argues that Uniłowski’s “drastic description of physiology…is meant to construct a symbolically marked space… it is a symbolic expression of his anthropological beliefs referring to the nature and man's duty. In this view a man is captivated by his physicality and can only strive to limit its power over himself…” In one scene Uniłowski juxtaposes “a gloomy sphere of biology (put in a blind kitchen) with the light which falls into the room through the window together with voices of a beautiful [woman] singing at work.” [26]

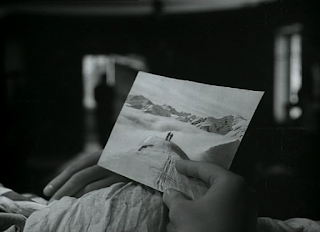

Zbigniew Uniłowski began writing the first chapters of One-Room Tenants in February 1931, at the residence of his longtime friend, the composer and pianist Karol Szymanowski. Szymanowski had been sick the previous years, sometimes barely able to write, undergoing treatment in Davos, Switzerland. In his letters to Uniłowski, Szymanowski expressed his wishes to have private accommodations. “I can’t stand guest houses, by reason of having to associate with strangers (especially unbearable women!).” It is not explicitly stated whether Uniłowski based the shared room and later ill state of Lucjan upon his own friend’s condition, although a forward to the letters written by Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz states: “Karol was slightly perturbed [by the novel], but he later calmed down: he believed in Uniłowski’s talent.” [12]

How are these aspects rendered in the film? The main apartment and other settings are often very dark (except for a brighter-lit museum interlude), the camera roaming and peering through interiors. Faces and objects of note are either prominent in the frame, or stuffed between the contours of other bodies or objects. Cinematographer Stefan Matyjaszkiewicz shot One-Room Tenants to convey tension and constriction. Though the film starts outside on the street, it rarely follows the characters outside after that, sitting still while the characters gaze outward through windows and doorways. Lucjan and other characters will be confined, in one room or another.

“Has’s adaptation updates the spatial topos of the body as a grave. The title room is a place of death for the main character. The disease and passing associated with this space allows the director to return to the theme of life resembling theatre. Above all, the room is a common space, characterised by a lack of intimacy and by exposure. Withdrawal means rejection of masks, opening and liberation. However, when it comes to time spent with other people, it is necessary to give up intimacy and accept constant assessment, which, unfortunately, excludes authenticity.” [8]

Their conversations skirt around issues, unable to confront matters of physical sickness or mental turmoil directly until it is too late for anything to change.

To recreate this ‘30’s era through dialogue, Dygat could have also drawn from his own experience as part of the bohemian milieu in pre-war Warsaw. The original novel was also inspired by the “Kwadryga” literary group. In 1928, “Kwadryga magazine became a monthly wide-range publication… Deep friendship relationships between members of both groups became a legend. The legend of “Kwadryga” was created mostly by the novel Wspólny pokój by Zbigniew Uniłowski, one of the most scandallizing novels of the pre-war priod.” [7, sic] Uniłowski also included the figure of author Isabela Czajka-Stachowicz [20], prominent in avant-garde circles and the café scene. She inspired the character of “The Leopard Woman,” [22] who enjoys ensnaring the attention of men. Her depiction is somewhat negative, but at least in the film she is allowed her own scene of reflection. These and other muted moments balance the fast, episodic scenes fading to and from black. One needs to pay attention to what underlies even the most petty-seeming plots in the film. By the time political intrusion takes away a visiting youth from the apartment, every aspect of the film is headed toward a final, cryptic glance at the audience.

One-Room Tenants and Farewells are often considered part of the Polish Film School movement, in which “filmmakers also tried blurring the lines between realism and symbolism of the characters, events, landscapes and objects on the screen. Even nowadays, the historians of cinema still dispute on the truth hidden beneath the images produced by the Polish film school; but they all agree [upon] the directors' method of expressing ideological reflection -- such as leaving the most important element ‘between the lines’…" [17]

Communist political domination in 1949 enforced Socialist Realism as the only approved mode of art in Poland. After Stalin died in 1953, this restriction became somewhat relaxed. The “Polish Film School (Polska Szkoła Filmowa)” arose between the relative stability of 1957 and 1963; confronting wartime experiences, generational clashes, and notions of Poland as a nation. Though Wojciech Has, even then, was noted for heading in a more independent direction, his output during this time is considered part of the movement.

While many of Dygat’s written works were aligned with Social Realism, he also moved along his own path. Dygat was one of several writers to resign from the Polish Communist Party in 1957 [16], after administrative crackdowns like the shutdown of Po prostu, a periodical popular amongst young intellectuals. Student meetings gathered to protest this decision were broken up, sometimes by force, by special militia. The literary journal Europa was also closed by the government even before publication of the first issue.

On March

14, 1964, Dygat joined others in science, arts, or politics in signing the

following “The Declaration of the Thirty-Four” (known in Poland as “List 34”):

[24]

"The reduction of printing paper allocation for books and periodicals and the enforcement of much stricter censorship create a situation which endangers the growth of Poland's national culture. We, the signatories, believe that the expression of genuine public opinion, the right to criticise, to discuss freely and to have access to unbiased information are all imperative ingredients of any progress. Therefore, moved by our social conscience, we demand that changes be introduced in the cultural policy of the Polish State which will accord with the spirit of its Constitution and promote the welfare of the nation." [21]

It was

sent to Prime Minister Jcizef Cyrankiewicz, but the Polish government denied

receiving the statement. However, the Polish People’s Republic still took

action. Some, if not all of the signatories were forbidden from broadcasting,

and their names were declared verboten on Polish radio. Productions were shut

down, passports and clinic services were denied. The writer who mimeographed

the declaration, Jan Lipski, was imprisoned for two days. Six hundred responses

in the press also condemned those who signed List 34, reportedly outraged at

this act of defamation inspired by Radio Wolna (Free) Europa. Yet the

government failed in convincing the signatories from withdrawing their names.

The extent of retaliation also varied from target to target. Dygat managed to

continue writing for print and film, and was one of the literary voices who

shaped the direction of many Polish films from the late ‘50’s onward. His

influence in social circles was such that the secret police were said to call

him “The Prince of Warsaw.” (Stanisław Dygat był przez bezpiekę nazywany

"księciem warszawskim".) [13]

The novel is narrated by the protagonist, a suspicious and over-analytical athlete named Marek Arens. At one point, Marek half-seriously muses, “Your parents compromised themselves in respect of various values. You all consider, therefore, that they’ve been compromised. But the values have been compromised too. They don’t want to admit that they themselves have been compromised and they attribute the compromise to you.” This is quite the indictment of the generations of One-Room Tenants and Farewells.

Disneyland takes place in livelier locations

than dank apartments or stuffy clubs or fading aristocratic mansions. It

features lively events in “public spaces frequented by the young and

fashionable, including a concert hall, a gallery and a sports club which also

serves as a venue for balls and parties.” [15] Yet Marek himself often

expresses two contradictory opinions, or states an ideal that he later betrays.

His generation also engages in disguises, hypocrisies, and stabs at honesty; at

the conversation games from the early romantic scenes of Farewells [13] and throughout One-Room

Tenants.

“The characters … typically tend to create an artificial world around them in which masks, multiple identities and confused emotions are commonplace. At the same time in Poland, however, the numerous possibilities open to the younger generation were being extolled. The game of masks and mirrors, mixing reality and illusion… was the favourite subject of the writer Stanislaw Dygat.” [6]

The film, directed by Janusz Morgenstern, is

less talky than the novel’s constant first-person narration, and feels more overtly

modern than the Has-Dygat adaptations or even the source novel. While Has

skillfully evoked the 1930’s and ‘40’s when directing Dygat’s scripts in the

‘50’s, Morgenstern “successfully portrays a very real picture of [contemporary]

Cracow, preserving the atmosphere and creating a true testimony of the period

for posterity.” [6] Jowita dips in

and out of a subjective lens but does not include the book’s narration. It is said

to be one of the few Polish film of the time clearly influenced by the French

New Wave [15], with split-second frame editing and sensual extreme close-ups. A

telephone’s ringing also anchors plot points with psychological effect. Outside

the concert, the soundtrack bounces with rock’n’roll and modern jazz. The meta

device of a film reel also becomes a brilliant catalyst for the memories and

regrets that propel Marek towards the conclusion.

After a

short plot introduction, we sweep into a concert where Khatchaturian’s waltz from the "Masquerade” suite plays. Marek falls into flashbacks that finally catch up to the concert

halfway through the film, making the novel’s time jumps easier for viewers to

follow. Then the film flashes back and forth again, extending past the concert.

There are less of the book’s ambiguity and mind games, but these seem cut for

time and cinematic flow, and do not undercut plot or themes.

Jowita consisted of the usually government-friendly

qualities of adapting a work by a Polish author and focusing on a story of

romantic escape and folly. The film still ran into censor trouble before

release. Dygat’s earlier political involvement might not have been the

cause.

“‘It is, perhaps, difficult for the Western spectator to understand the challenge that the film and its heroes makes to members of government…This type of psychological and sentimental interplay and this fondness for freedom from commitments and responsibilities was common to most of the youth in other countries, where it was in no way considered subversive. However, in a country where the role of films was considered to be to testify to ideologies, portraying official social truths, such “charmers” could only be a source of irritation to many.’” [6]

Even

avoiding political themes could court government trouble in this time.

Marek has

many affairs with women, but can’t forget his one conversation with Jovita,

whose “Turkish” costume only revealed her eyes. His boxing coach Szymaniak (in

the novel, Marek’s doting stepfather) killed himself after a doomed

relationship with the prostitute named “Lola Fiat 1100,” a character thought by

Marek to be more predatory than someone like “The Leopard Woman” in One-Room Tenants. This is the basis for a disturbing view of

women as mysterious, interchangeable until proven unique, exotic like the

costumes at the sports club ball.

Yet both the book and novel position Marek’s perspective as dangerous, and the women in the story hold their own as characters. One woman even confronts him in the final scene. His feelings are jumbled by the conviction, shared by Polish Romantics, that love is a minor pursuit for a man, unlike nobler affairs like competitive or intellectual pursuits. Though he is close to proposing marriage at one point, he is reluctant give in to what he sees as the domestic inclinations of women, which trapped his athletics coach and could have led to Syzmaniak’s suicide. “Marek preferred an imaginary (limerent) object of desire over a real woman or even over several women with whom he had affairs and, ultimately, he chose nonlove.” [15] He might tell himself that he despises hurting women, but his misogyny eventually guides his hand to violence. Like the protagonists of Farewells and One-Room Tenants, Marek’s aspirations and personal ideals will remain unfulfilled.

Yet both the book and novel position Marek’s perspective as dangerous, and the women in the story hold their own as characters. One woman even confronts him in the final scene. His feelings are jumbled by the conviction, shared by Polish Romantics, that love is a minor pursuit for a man, unlike nobler affairs like competitive or intellectual pursuits. Though he is close to proposing marriage at one point, he is reluctant give in to what he sees as the domestic inclinations of women, which trapped his athletics coach and could have led to Syzmaniak’s suicide. “Marek preferred an imaginary (limerent) object of desire over a real woman or even over several women with whom he had affairs and, ultimately, he chose nonlove.” [15] He might tell himself that he despises hurting women, but his misogyny eventually guides his hand to violence. Like the protagonists of Farewells and One-Room Tenants, Marek’s aspirations and personal ideals will remain unfulfilled.

Works Consulted

[1] "Cloak of

Illusion." The MIT Press. Print.

[2] Davies, Norman. Heart

of Europe: The Past in Poland's Present: The Past in Poland's Present.

Oxford University Press, 2001. Web. 17 Mar 2014. <

http://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=lang_en&id=lMQei5CPZUgC&oi=fnd&pg=PP2&dq=%2B%22Juliusz+S%C5%82owacki%22&ots=JtPYeUDPCk&sig=eMe2XnCBCROUSVc9RQ3_IiSIEmE#v=onepage&q=%2B%22Juliusz%20S%C5%82owacki%22&f=false>

[3] "Do you

remember, it was fall." Translation of "Pamiętasz, była

jesień" by Sława Przybylska from Polish to English. Lyrics Translate,

30 June 2011. Web. 15 Apr. 2014.

.

[4] Dygat, Stanislaw.

Cloak of Illusion. Trans. David Welsh. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press,

1969. Print. 15 Feb 2014.

[5] "Elliptic

worlds of Wojciech Jerzy Has: Petla (Noose) – Wspolny pokoj (One room tenants)."

Kinoglazorama Spectacular. 20 Mar 2011. Web. 2 Jan. 2014.

[6] "Festival Lumière - "Jowita"." Lumière 2011: Grand Lyon Film Festival. Institut Lumière, 2011. Print. .

[7] Gałczyński, Mikołaj. "Life and Works of Konstanty Ildefons Gałczyński." Official Website of Konstanty Ildefons Gałczyński. 2008. Web. 4 Apr 2014. .

[8] Grodź, Iwona. "One Room Tenants." ARCHIVE - 10th Era New Horizons International Film Festival. Stowarzyszenie Nowe Horyzonty, 2010. Web. 4 Apr 2014. .

[9] Has, Wojciech, dir. Farewells (Lydia Ate the Apple) (Pożegnania). 1958. Web. 14 Dec 2013.

[10] Has, Wojciech, dir. One-Room Tenants (Wspólny pokój). 1959. Web. 4 Jan 2014.

[11] Helman, Alicja. "The Masters Are Tired." Canadian Slavonic Papers/Revue Canadienne des Slavistes 42.1/2 (2000): 99-111. Web. < http://www.jstor.org/stable/40870137>

[12] Hughes, William,

ed. "Zbigniew Uniłowski: ‘Letters from Karol Szymanowski’ (‘Wiadomości

Literackie’, 1938, nr.1)." The Chronicles of Doctor Hughes. 03 Nov

2012. Web. 4 Apr 2014.

[13] Kowalczyk,

Janusz R.. "Stanisław Dygat." Culture.pl. 2012. Web. .

.

[14] Mazierska, Ewa.

"Existentialism and socialist realism in the early films of Wojciech

Has." Studies in Eastern European Cinema 4.1 (2013): 9-27. Web. <http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/intellect/seec/2013/00000004/00000001/art00002>

[15] Mazierska, Ewa. Masculinities

in Polish, Czech, and Slovak Cinema: Black Peters and Men of Marble. New

York: Berghahn Books, 2008. Pp 153-155. Web.

[16] Michnik, Adam. The Church and the Left (Koṡciół, lewica, dialog). Ed and trans. David Ost. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993. 85. Web.

[17] Miczka, Tadeusz. "Cinema Under Political Pressure: A Brief Outline of Authorial Roles in Polish Post-War Feature-Film 1945-1995." Trans. Andrzej Cimala. Kinema (1995). Web.

[18] Miłosz, Czesław. "The Novel in Poland." Daedalus 95.4 (1966): 1004-1012. Web. < http://www.jstor.org/stable/20027015>

[19] Morgenstern, Janusz, dir. Jovita (Jowita). 1967. Web. 23 Mar 2014.

[20] Pawłowska, Monika. "Izabela Czajka-Stachowicz in three perspectives: as literary character, friend of artists and heroine of her fictionalized autobiographical books." Archive of Theses. University of Warsaw, 2 Dec 2013. Web. .

[21] "Polish Intellectuals Under Pressure." The Tablet 18 Apr 1964. Web. .

[22] Nikodem, Jakub. “Izabela Czajka-Stachowicz, "Moja wielka miłość".” Culture.pl 22 Jul 2013. Web. .

[23] Świdziński, Wojciech. "Farewells-What does Wojciech J. Has did Adieu to?. ("Pożegnania" - z czym się żegna Wojciech J. Has? )" Kwartalnik Filmowy 57-58 (2007). Web.

[24] Szubarczyk, Piotr. "14 marca 1964: List 34." Kalendarz polski codzienny. Wolna Polska. 2014. Web. .

[25] Toepplitz, Krzysztof-Teodor. "The Films of Wojciech Has." Film Quarterly 18.2 (1964): 2-6. Web.

[26] Wierzbicka-Trwoga, K. "Breaking the taboo of secretion on the example of Zbigniew Unilowski’s ‘Sharing a Room’." Pamiętnik Literacki 98.3 (2007): 63-73. Web.

No comments:

Post a Comment